From Ancient Shell Mounds to Modern Reefs: Restoring Oysters in Brevard County

The story of oysters in the Indian River Lagoon is one of abundance, decline, and hope for renewal.

1. A Rich History of Oysters in the Indian River Lagoon

Thousands of years ago, long before the shoreline was dotted with docks and seawalls, the Ais people lived along the lagoon’s edge. They harvested oysters and clams for food and tools, leaving behind towering shell mounds called middens.

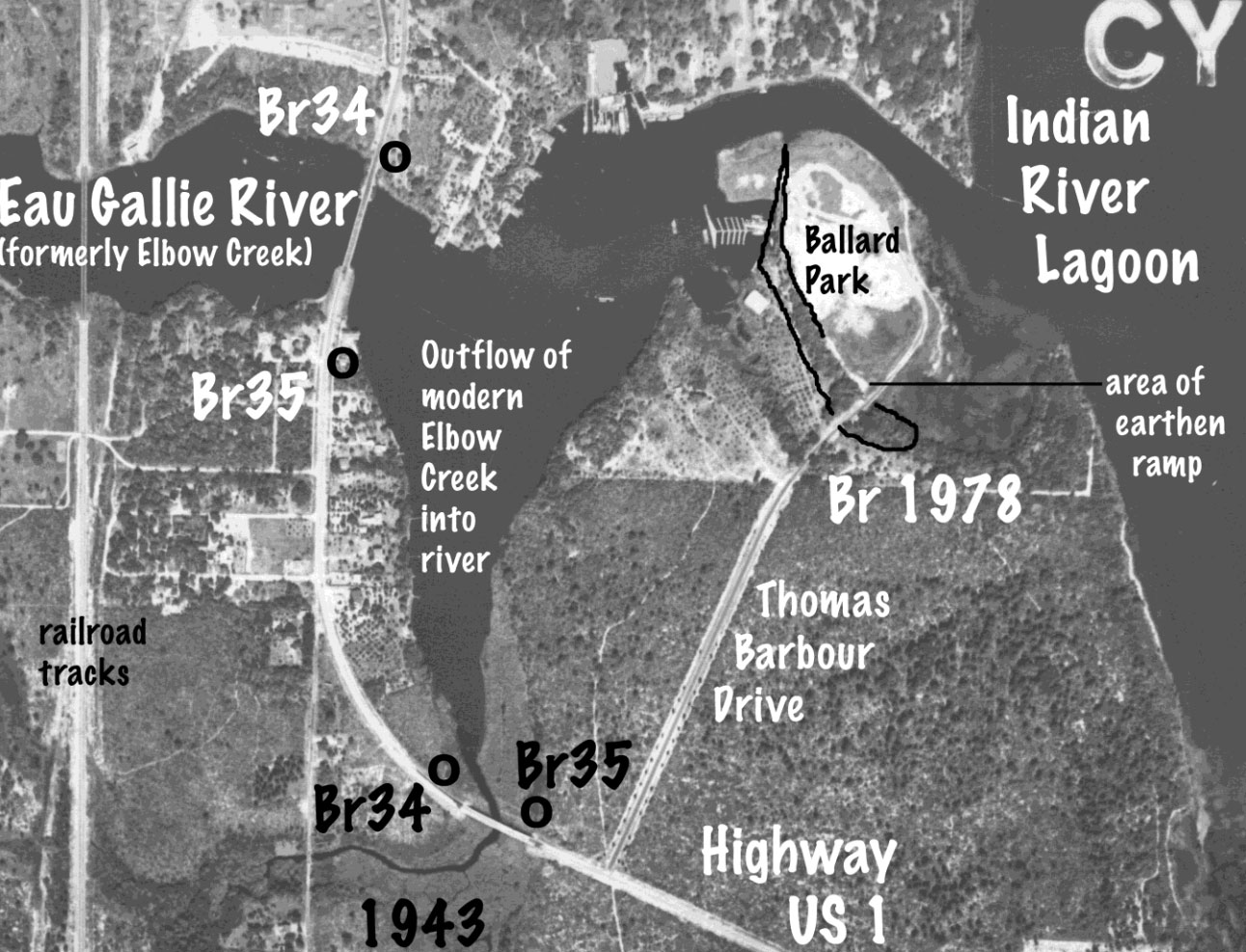

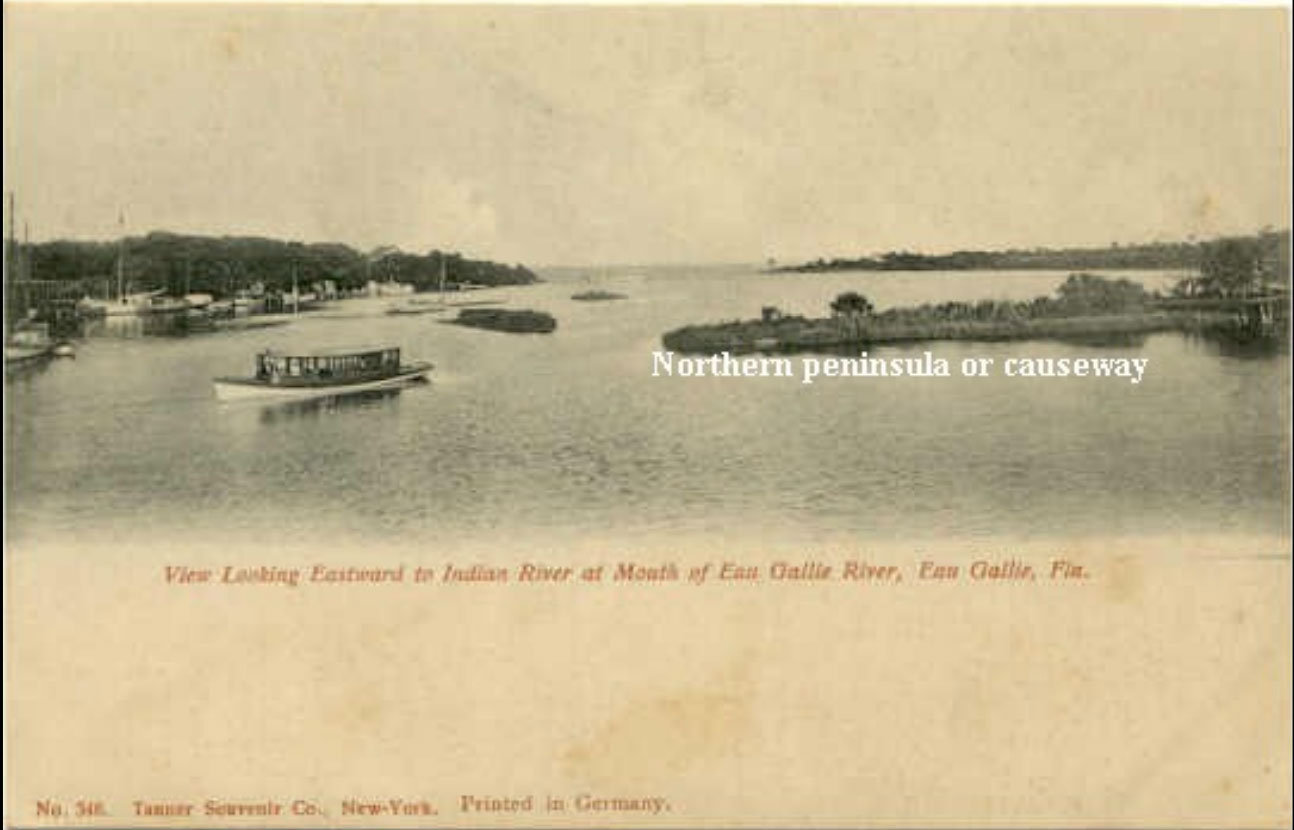

One of the largest, the Pentoaya Midden, covered 1.8 hectares (4.5 acres) near where the Eau Gallie River meets the Indian River Lagoon in present-day Melbourne. Layers of oyster and clam shells mixed with pottery, bones, and other artifacts tell of a place rich in life and activity. Spanish maps from the 1600s show Ais villages in this very spot, evidence of a community sustained by the lagoon’s bounty.

2. The Decline of Oyster Habitat

Over time, the landscape changed. Research in Mosquito Lagoon, north of Brevard, shows oyster habitat declined by about 24% between 1943 and 2009.

The causes were many: seawalls and riprap now line roughly 64% of Brevard’s shoreline, removing natural spaces where oysters could grow. Fertilizer, septic systems, and stormwater runoff carry nutrients that feed algae blooms, reducing oxygen and smothering reefs. Freshwater from canals alters salinity levels, disrupting reproduction cycles.

3. Why Oysters Matter

Oysters are more than food—they’re architects of the lagoon’s ecosystem. A single oyster can filter up to 30 gallons of water a day. Oyster reefs shelter fish and crabs, and oyster reef structures help protect shorelines from erosion.

4. Restoring What Was Lost

Today, the story is shifting toward recovery. In Brevard County, restoration efforts unite science, volunteers, and community support:

- The Save Our Indian River Lagoon Program (SOIRL) is investing in oyster restoration because oysters are natural water filters and habitat builders. Oyster bars provide shelter for more than 300 species of fish, crabs, and other wildlife. Working with partners like Brevard Zoo’s Restore Our Shores and the University of Central Florida, SOIRL helps build and monitor reefs using recycled shell and innovative designs. The program’s plan includes 28 oyster restoration projects, strategically placed along both natural and hardened shorelines to reestablish oysters where they once thrived. Guided by an adaptive strategy, SOIRL tracks growth and habitat benefits to refine approaches over time. To date, more than 80,000 square feet of oyster habitat have been restored across Brevard County. As these reefs expand, they filter more water, support more marine life, and act as natural breakwaters—laying the foundation for a healthier lagoon ecosystem that benefits both people and wildlife (Brevard County SOIRL Project Plan).

- City-Level Examples – Local shoreline projects demonstrate results on the ground. In Cocoa Beach, the McNabb Park living shoreline incorporates oysters and mangroves and is estimated to remove 96 lbs of nitrogen and 32 lbs of phosphorus every year (City of Cocoa Beach). Watch a video about McNabb Oyster restoration here: YouTube

- Indian River Lagoon National Estuary Program (IRL NEP) supports regional projects, including a 2007 partnership with The Nature Conservancy, UCF, and Canaveral National Seashore to restore reefs in Mosquito Lagoon.

But it’s not just science—it’s community. At the heart of restoration efforts is Restore Our Shores (ROS), the Brevard Zoo’s conservation program. For nearly a decade, ROS has connected everyday people to the lagoon’s resurgence.

- Oyster Gardeners: Local lagoon-side residents grow young oysters off their docks, nurturing them for six to nine months. These “spat” eventually move to reef sites during a special “Homecoming,” where restoration communities come alive. This program has already produced over 500,000 oyster juveniles, illuminating the best spots for new reef planting.

- Building with Purpose: Volunteers help assemble gabion reefs—metal cages filled with recycled shell—and newer “corrals,” shell-enclosed structures that mimic reef conditions. In one corral trial near Melbourne Beach, volunteers helped cultivate 40,000 oysters, and the reefs became homes for more than 20 species.

- Digging Deeper: With support from Restore America’s Estuaries, ROS is studying oyster reproductive health and larval settlement across Brevard County. Volunteers help sample oysters and track water quality. Earlier this year, ROS constructed half an acre of oyster habitat and is monitoring it under SOIRL’s five-year plan.

- Ways to Pitch In: Whether you live on the lagoon or not, there are meaningful ways to join in. Volunteer roles include oyster gardening, reef building, shell preparation, mangrove planting, and more. The 2025–2026 oyster gardening season is now open for sign-up, and ROS also hosts supply preparation meetups for oyster habitat materials.

5. How You Can Help Write the Next Chapter

The story of oysters in Brevard County isn’t finished. You can help shape its future:

- Avoid using fertilizer from June 1–Sept 30; if you can't eliminate use year-round, make sure to choose zero-phosphorus, 50% slow-release nitrogen formulas the rest of the year.

- Keep yard waste out of streets and drains.

- Pick up pet waste to prevent bacteria and algae-feeding pollution from entering waterways.

- Reduce runoff with rain barrels, rain gardens, or permeable pavers.

The lagoon’s past reminds us of its resilience—and with community action, we are turning the tide. Join Lagoon Loyal to find more lagoon-friendly tips, tricks, and ways to get involved. Together, we can help oysters once again thrive in the waters of our Indian River Lagoon.

References

Brevard County & Local Programs

- Brevard County Save Our Indian River Lagoon Program – Save Our Indian River Lagoon

- Brevard County Natural Resources Management Department – Oyster Suitability and Success Plan (2020)

- Brevard Indian River Lagoon Coalition – Habitat Restoration

- One Lagoon (IRLNEP) – Episode 20: Leading the Way Toward Oyster and Shoreline Restoration in Mosquito Lagoon

- Restore Our Shores (Brevard Zoo) – Conservation Continues: Completing Our Largest Living Shoreline

- Restore Our Shores (Brevard Zoo) – Studying Oyster Health in the Indian River Lagoon

- Restore Our Shores (Brevard Zoo) – Oyster Gardening

Regional News & History

- ClickOrlando News 6 – Researchers Monitor Oyster Health to Restore Indian River Ecosystem

- Space Coast Daily – Space Coast Community, Nature Join Forces to Heal Indian River Lagoon

- Indian River Journal (2008) – Locating the Ais Indian Town of Pentoaya

- Historical Marker Database – Winter-Time Ais Indian Town of Pentoaya

Research & Science

- University of Central Florida – Trends in Oyster Habitat Change in Mosquito Lagoon, 1943–2009 (Shell et al., 2015)